Introduction

The most significant element to the discussion of text-criticism and Bible translations is that of epistemology. Christians recognize two forms of revelation, natural and special. In the first place, men and women know things because they are made in the image of God, and can use their reasoning to come to conclusions. This natural reasoning and sense observation is not sufficient to bring anybody to a saving knowledge of Jesus Christ. Secondly, in special revelation, God speaks so that men may know His revealed will. The question we have to ask ourselves as it pertains to the textual discussion is, “Is my epistemological starting point in line with what God has revealed in Scripture?”

One of the purposes of this blog is to demonstrate that “modern text criticism” begins epistemologically in a different place than the Scriptures. That does not mean that self-identifying Evangelicals who engage in text-criticism necessarily have anti-Scriptural epistemological starting points, just that the various methods, as defined, assume a certain epistemological starting point that is incompatible with Scripture. In other words, one can employ modern text criticism from a Christian epistemological perspective, and still be starting from the wrong place by adopting some or all of the axioms of a method that assumes no such foundation.

For example, in mainstream textual criticism, the most popular and accepted position is that the Scriptures went through a recension, or editing process, which resulted in what is commonly called the Byzantine text platform. Some say this happened all at once (Lucian), and others say that this happened gradually (Wachtel). The concept of a Scriptural recension is not a historical fact, or a neutral fact, it is an interpretation of data which has an epistemological starting point. That starting point is that the Scriptures were not kept pure in continuous transmission. In order to arrive at this conclusion, one must assert that the Scriptures changed dramatically in their transmission to explain why the majority of the later manuscripts look very different from the early minority of manuscripts. The reason that this is an epistemological problem is because the extant evidence in the 21st century cannot demonstrate, without a shadow of a doubt, either of these perspectives.

Evidence or Epistemology?

There is no way to prove by way of extant data that the original text of Holy Scripture looked like Vaticanus, or P75, or any of the commonly called Alexandrian manuscripts. In the same way, there is no way to prove that family 35, or the TR, or the Tyndale House Greek New Testament exists in exactly the same form as the originals. The same goes for individual readings within the manuscript tradition. Even if we had 1,000 copies of Mark from the fourth century that looked exactly the same, evidence driven models cannot validate that those copies are accurate to the original because we don’t have the original. That does not mean that we cannot know what the original New Testament said, just that the modern text criticism in the 21st century is not a justifiable means to determine the text. So then, in the absence of sufficient building materials for a reconstruction effort, epistemology is without question, the most important component to this discussion.

If the Scriptures teach that the Word of God will not fall away, and that in every generation, God’s people had access to that pure Word, then such ideas as a recension cannot even be entertained without violating that epistemological principle. On the same premise, any idea that supposes that a small sample of early extant manuscripts represents the scope of the whole of the manuscript tradition, or at least does so in part, also is a violation. In order to adopt an Evangelical epistemology and a modern critical epistemology, one must interpret the conclusions of modern criticism, which violate Christian epistemology, by Christian epistemological foundations. This is perfectly exemplified in the discussion of creation. If Darwin’s premise (or something similar) is adopted as the epistemological starting point, then Christians must make sense of Genesis 1-12 in light of that starting point. Rather than rejecting Darwin and friends, evolutionary theory is adopted as a hermeneutic principle rather than the Scriptures themselves. The result is the rejection of a literal creation, a literal Adam, a literal flood, and so forth. This is yet another issue that is said to be doctrinally “neutral,” I’ll remind you.

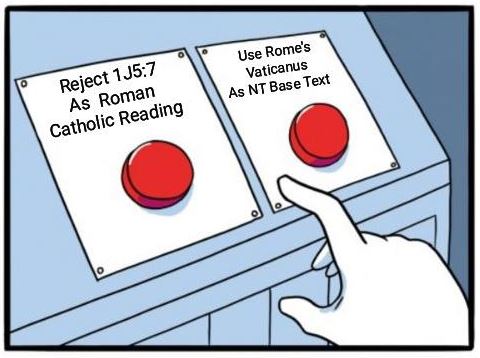

It would be irresponsible to say that adopting any form of theistic evolution is purely based on examination of evidence and making the best determination possible from that evidence. Rather, one must say that from a certain epistemological starting point, the data must be interpreted in this way or that. In the same way, extant manuscript data is not examined neutrally. One is not simply making the “obvious conclusion based on the data” when they reject 1 John 5:7, they are making an “obvious conclusion based on the data” from one particular epistemological starting point. If one wants to make the claim that a lack of evidence for 1 John 5:7 in many manuscripts demonstrates that all manuscripts before those didn’t have it, he is doing so from his epistemology or interpretive lens.

A manuscript says nothing absolute regarding the manuscript it was copied from, unless one makes certain assumptions. If the manuscript is truly the only guide, then the only thing that can be determined is that this manuscript, at this point in time, looked this specific way. The scribe of that manuscript could have easily removed a reading from his exemplar, which was then copied forward. One can make observations of scribal habits of one particular manuscript, but the scribal habits of one manuscript says nothing about the exemplar from which the scribe copied. If there is an extant archetype of that manuscript, more can be said, but in the case of the Scriptures, there is not a continuous line of transmission that can be observed, so any difference form one text to another must be interpreted from an epistemological starting point. Did scribes copy carefully, or did they not? Are the “original” readings longer, or shorter? Do earlier manuscripts contain more errors, or less? Since there is no extant pure line of manuscripts that goes back to the apostles, the amount of “neutral” observations that can be made about a manuscript is extremely limited. Thus, a Christian should be chiefly concerned with whether or not the lens he is examining evidence with is that which comes from the Scriptures. Anything else is a critical perspective of the Christian Scriptures as interpreted by a Christian.

Epistemology Has Consequences to the Text of Scripture

The reason that those in the Received Text camp perceive modern critical text positions as so “dangerous” is because of the epistemological starting points of modern critical methods, not necessarily the Christians who adopt these methods. These methods, regardless of who uses them, do not assume basic Christian epistemological realities. An example is how evangelicals affirm that the Scriptures were “without error in the original” and also adopt the modern critical perspective that grammatically difficult readings are to be preferred as earlier than grammatically smooth readings. A system which does not comport with Scripture is not something that needs to be “redeemed,” but rejected.

“Text criticism” itself is not the problem, it is the type of text criticism that is the problem. It was recently said that the Reformation era printed texts, and possibly all copied texts, were simply all “reconstructed texts” from the past. The Received Text position then is no different than modern text criticism other than the selected “reconstructed text” is different. That is to impose an epistemological concept upon the men of the past that simply did not exist prior to the age of reason in any meaningful way within the bounds of orthodoxy. One of the greatest errors of modernity is believing that “we know better” or to impose our modern epistemology upon men of the past. This is especially demonstrated when modern interpreters of historical theologians read their perspective into men of the past.

It is often the case that the most “powerful” arguments against the Received Text are simply unfounded assertions that can in no way be substantiated in the kind of way that the argument requires. For example, it was recently said that the burden of proof is equally upon somebody to prove a reading original as it is to prove it unoriginal. This assumes that without reconstruction of every line of the text, there simply wouldn’t be a Bible, and that Scripture is guilty until proven innocent. If the belief is that the people of God had the pure Scriptures in every generation, then the burden of proof is demonstrably upon this generation to prove a Scripture not original from the previous generation. When the extant evidence is examined, it does not seem that engaging in such a practice is warranted, or profitable in any way. Can extant evidence demonstrate a reading to be original or unoriginal? Absolutely not. Therefore it is far more important to examine the epistemology from which a claim flows in the textual discussion. Is it the job of Christians today to determine the text of Scripture from evidence, or receive the text of Scripture from the previous generation? These are epistemological questions, not text critical ones.

The Epistemological Foundations of Both Sides

In order to cut directly to the heart of the issue, the most fundamental epistemological starting point of modern text criticism is that there was no continuous line of transmission of the text, that the text was incorrectly identified at the advent of the printing press, and as a result, modern Christans and non-Christians must work together to reconstruct the text as it existed prior to a major recension, or perhaps various gradual recensions. This task is of such a tall order that after nearly 150 years, no method and no scholar has ever achieved success in reconstructing the original, and those still working are increasingly skeptical that that can actually be done. Despite this, the primary purpose of the extant data is still seen as adequate building materials.

On the other hand, those in the Received Text camp begin by stating that the immediately inspired Word of God has been “kept pure in all ages.” The extant data is not to be used as building materials today, because nothing needs to be built. The purpose of the extant data then serves the people of God in a different way than is assumed by modern critical methods. The task of the church today is not to reconstruct the New Testament, but to receive and defend the text handed down from the previous generation. This is the major disconnect between those in the Received Text camp and modern critical camp. In the modern critical perspective, since the text is assumed to have fallen away such that it needs to be rebuilt, the extant evidence is purposed to demonstrate that the Received Text is not pure, and thus to justify reconstruction. Since the text from the previous generation is deemed impure, extant evidence resembling the text of the TR must also be counted as such, discrediting nearly all of the extant New Testament data. If it could be agreed upon that the responsibility of the church is reception, not reconstruction, then the question of determining “which TR?” would not be one that serves a mere polemic purpose. The church should be rallying around receiving a text, not dividing over which modern reconstruction is the most accurate, and why the Received Text is wrong.

While it is easy to think that the first assumption of the modern critical perspective is that the TR is in error, it is that God did not continuously preserve the Word in every generation. In other words, it is not a data driven assumption, it is an epistemologically driven assumption. It is an assumption that rests almost entirely on the claim that what is extant today represents what the church had historically. In order to conclude that the TR is in error in the first place, one must assume that the extant data available today is also better than the data available in Europe at the time of the advent of the printing press, and even further that the data available in every generation before that could not have looked like the TR. One has to discount the reality that countless thousands of manuscripts have been destroyed since the 1st century. It is a terribly rash conclusion to make, considering how dangerous the outcome of that conclusion is.

There is simply no way to responsibly say that the extant data today is “better” than the extant data available during the times when that extant data was being used and copied. So when somebody makes the claim that “the church didn’t read this in the text for the first 1,000 years,” they are doing so from an entirely assumptive and arbitrary place. They are interpreting extant data through an epistemological lens which says, “I know for sure that we know more,” even though that is a lofty claim to make based on the history of the text as it exists in extant manuscripts. Is it not a fair assumption to make that there were more than three manuscripts of Revelation circulating in the third century, and that the people of God knew what was in those manuscripts? And yet the modern critical method says, “Yes, we know more with our three manuscripts about Revelation as it existed in the third century than those who used manuscripts of Revelation in the third century.” Such a perspective is clearly driven by epistemological assumptions.

Conclusion

In this discussion, I have found that epistemology is rarely addressed. It is easier to focus on extant data rather than discussing the lens by which men are viewing that data. Yet, if the lens that the data is viewed is flawed, then the conclusions made about that data can also be flawed. And if that lens is in opposition to Scripture, it is necessarily flawed. The common justification for approaching the Bible from a reconstructionist perspective is that, “God didn’t keep His Word pure, so we shouldn’t impose that perspective on the text.” Yet, there are a fair number of verses that teach that God’s Word will not pass away. Matthew 5:18 affirms down to the jot and tittle. Jesus connects the fulfillment of His ministry with His words (Matthew 24:25). The Psalms constantly speak of the Law being perfect, pure, and refined. The Scriptures say that “all Scripture” is necessary for matters of faith and practice, not just “some.”

If we can agree that God did promise to continue speaking in the Scriptures, and that those Scriptures would be preserved until the Last Day, then a meaningful dialogue can take place on how we define the precision of that preservation. This conversation cannot take place currently, however, because those on both sides stand on different epistemological foundations. There is no common ground to be had between a person who says the Word of God is preserved and a person that says that the Word of God is not preserved. If the goal is to give confidence to the people of God in their Bible, it does not follow that we do so by starting with the premise that we have not yet successfully found God’s Word. And if our goal is to approach matters of text criticism faithfully, it does not follow that in our text critical axioms we assume that the earliest texts we have were not grammatically harmonious. The problem is not with “text criticism,” it is with epistemology, and the type of “text criticism” we advocate for and support.