Introduction

I recently read a thorough and fair defense of the Johannine Comma (1 John 5:7) which reminded me of how the approach of many Christians in the modern church is absolutely backwards when it comes to Scripture. In today’s world of Modern Textual Criticism, Christians seem to take a backwards approach when seeking to determine if they should accept a textual variant as authentic. The method employed by the author of the linked article demonstrates, in my opinion, how textual data should be viewed, so please read the article prior to this one. In this article, I will comment on the two approaches to textual variation and conclude by explaining why I believe the approach taken by the exemplar author is correct.

Method 1: Modern Textual Criticism

I have spent a great deal of time and word count (222,197 words to be exact) on this blog explaining the methods and theology of the Modern Textual Critics and advocates. I have pointed out, using the words of the textual scholars, that there is no Modern Critical Text, there is no end in sight to the current effort, and adopting the Modern Critical Text means also to reject providential preservation. In all these words, I have yet to describe the approach of the Modern Textual Critic and advocate.

When a defender, advocate, or scholar of the Modern Critical Text approaches a place of textual variation, they do so by first questioning its authenticity. Practically speaking, a variant is to only be questioned if the scholars who produced the NA/UBS platforms have called it into question. That is not to say that others in history haven’t called such texts into question prior to the 20th century, just that these questions are exemplified in the modern critical texts. The reason this is problematic is that there is no consistent application of this skepticism applied to every line of Scripture.

See, the epistemological foundation for the Modern Textual Critic, according to Dan Wallace and his colleagues, is that we don’t have what the authors originally wrote, and even if we did, we wouldn’t know it.

“We do not have now – in any of our critical Greek texts or in any translations – exactly what the authors of the New Testament wrote. Even if we did, we would not know it.”

Dan Wallace. Myths and Mistakes in New Testament Textual Criticism. xii.

This kind of foundation cannot conveniently stop at our favorite three passages. It must apply uniformly across the whole text of the New Testament. If 200 years of textual transmission which saw such a great change to the text from the “Alexandrian” text form to the “Byzantine” text form, then the first 200 years of textual transmission, of which we have basically zero extant evidence for, could also be equally or more significant. That is to say, our 200 year gap in the manuscript data in the first 200 years of the church is enough of a gap to call into question every single passage of the New Testament. This is the logical end of the Critical Text position. There isn’t a single line of Scripture that can be said to be 100% authentic to the pen of the apostolic writers, according to the Modern Critical Text advocate. This is further evidenced by the fact that there is not a single textual scholar or apologist that will lay claim to any specific percentage or list of authentic passages.

So when an advocate of the Modern Critical Text challenges a textual variant, they do so selectively and arbitrarily. Once they have identified a passage, verse, or word that they do not believe original, the goal is to then “disprove” that the reading was authentic. The text is on trial, and the Modern Critical Text advocate is the prosecutor. It is not a question of “Is this text authentic?”, it is a question of, “Why is this text inauthentic and how did it get there?” If they were consistent, they would apply this same approach to every line of Holy Scripture, and have no evidential reason to accept one reading or another. The evidential foundation for their approach is based upon manuscripts that are dated 200 years or more after the New Testament was written without any supporting evidence that those texts date back to the Apostles. This is the fatal flaw in Modern Textual Criticism – there is nothing that ties their text back to the original, and there never will be. That is why approach matters.

Method 2: Preservationist

In contrast to the first method, the Preservationist perspective approaches places of textual variation with the assumption that the original has been preserved, and it can be easily discerned. The preservation of Scripture did not stop with Codex Vaticanus, it carried on through the middle ages and into the Reformation when the world could finally print and mass distribute texts. There is a reason the vast majority of extant manuscripts do not look like Vaticanus or the Modern Critical Text. The church, through transmission and by God’s providence, kept the text pure. Therefore, if a text made it to the mass distribution era of the church, it had been passed along by the era that came before it. Since the church was by and large divided into two represented by the East and West, the combination of these texts yielded the original. That is why the advent of the printing press, the fall of Constantinople, and the Protestant Reformation is such a significant time in church history. It was the first time the church had authentic texts that were being used in one place with the ability to combine them and distribute them church-wide.

So then, to the Preservationist, the question is not, “Is this text authentic?”, it is, “Why did the people of God understand this to be authentic in time and space?” Thus, the burden of proof is not placed on a smattering of early manuscripts that have been in favor for the last 200 years. The Preservationist’s chief effort then is to support the text that has been handed down, rather than question its validity at every place disagreeable to the Vatican Codex. The assumption is that God preserved the text, and we have it. It is a matter of defending what is in our hands, rather than reconstructing what is not in our hands. Once you accept the premise that the Bible has fallen into such disarray that it must be reconstructed, there is not a single passage of Scripture that cannot be called into question. Further, there is no way to validate that any conclusion on a given text speaks conclusively about the original text itself. That is why the current effort is focused on the initial text, not the original. What can be proved is limited to hundreds of years after the Apostles, and even then, “proved” is much stronger language than textual scholars are comfortable with.

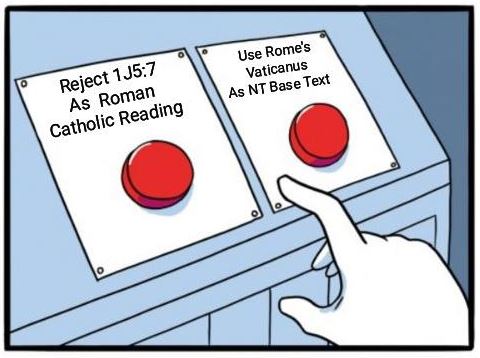

1 John 5:7 is a perfect example where the two approaches come to two separate conclusions. Since 1 John 5:7 is thinly represented in the extant manuscript data, the difference in conclusion on the text is really a matter of approach. The Modern Critical Text crowd has already admitted that even if 1 John 5:7 was original, they wouldn’t know it, so any conclusion jumping off from that point is irrelevant. Nothing they determine can actually be concluded by textual data, and so they engage in story telling. “The passage was brought up from a footnote. It was added to bolster the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity.” Yet they do so without any direct evidence claiming this is what happened. Strangely enough, these critics also conveniently reject any evidence offering explanation as to why a passage is not in certain manuscripts. The bias in Modern Textual Criticism to favor manuscripts that have been historically rejected is strong.

If we approach this text from a preservationist perspective, we see that the wording is referenced by Tertullian (2nd century), Origen (3rd Century), Athanasius (4th Century), Priscillian (4th Century), Augustine (4th Century), and directly quoted by Cyprian (3rd Century). The direct quotations can be found in this article. This is not the only support for the passage, but it is enough for the preservationist to support 1 John 5:7 as original. It is enough to defend the text we have in hand, and the text handed down to us from the Reformation era. Accepting the Johannine Comma is not an issue of evidence, because the evidence exists. It is a matter of Bibliology and approach.

Just because a manuscript is surviving today does not mean it is the only manuscript to ever have existed. Textual scholars and apologists carry on about how many Bibles were destroyed during times of persecution and war and fail to acknowledge that those destroyed manuscripts could very well have contained the passages they reject today. The abundance of quotes and references to the passage, along with the reception of the text by our Protestant forefathers informs us that manuscripts with the passage existed, we just don’t have them today. Paradoxically, this is not enough for Modern Critical Text advocates to adjust how they approach textual data. The fact that we do not have an abundance of handwritten manuscripts in 2021 should not be a surprise, seeing as handwritten manuscripts of the Bible haven’t been produced or used in over 400 years. The Protestants and those that came after believed 1 John 5:7 to be original, and even claimed that authentic copies in their day had the passage. They even recognize that there was a time where manuscripts did not have the passage. See Francis Turretin commenting on the three major variants still debated today.

“There is no truth in the assertion that the Hebrew edition of the Old Testament and the Greek edition of the New Testament are said to be mutilated; nor can the arguments used by our opponents prove it. Not the history of the adulteress, for although it is lacking in he Syriac version, it is found in all the Greek Manuscripts. Not 1 John 5:7, for although some formerly called it into question and heretics now do, yet all the Greek copies have it…Not Mark 16, which may have been wanted in several copies in the time of Jerome (as he asserts); but now it occurs in all, even in the Syriac version, and is clearly necessary to complete the history of the resurrection of Christ”

Francis Turretin. Institutes of Elenctic Theology. Volume 1. 115.

See, an honest scholar would admit that the position of the Protestant and Post-Reformation church was that of the Preservationist. It was that of the TR advocate. Behind closed doors, many prominent modern scholars admit this, they just don’t like it. For more quotations on the passage from historical Protestant theologians, see this article here.

Conclusion

So I argue here in this article that there is a stark difference in approach between the Modern Critical Text advocate and the Preservationist and that the difference in approach is far more significant than the textual data itself. Those in the Modern Critical Text camp are determined to answer “Why is this not Scripture and how did it get in the text?”, whereas the Preservationist says, “This is in our text, how do we support it?” The interesting thing is, that if the Critical Text advocate took the approach of a Preservationist, they would find that the burden of proof they accept for many passages would be enough to accept John 7:53-8:11, Mark 16:9-20, and 1 John 5:7. The issue is not evidence, it is approach.

If you approach a text with the belief that it is not Scripture as the Modern Critical Text crowd does, you will find that it is not Scripture in your eyes. Yet, as with all claims based on extant textual data, there is no warrant to come to any conclusion. That is why the scholars never do. If you approach the text with the belief that it is Scripture, you will find the the evidence to support that claim. Since the belief of the Preservationist is not based on extant data, the extant data is merely a support, not a foundation. The Preservationist recognizes that extant data will never “prove” the Bible. It is a theological position similar to the resurrected Christ. The most important question is not “what evidence do you have?”, it is, “What does the Bible say?” If it is preserved, than the conclusion is that 1 John 5:7 is original. If Scripture is not preserved and needs to be reconstructed, than the conclusion is not only that 1 John 5:7 is inauthentic, but so is all the rest of Scripture. There is nothing conclusive against 1 John 5:7 that cannot also be conclusive against all of the rest of Scripture. This is inevitable considering the significant gap in our extant manuscript data from the apostolic period to the 3rd century.

This is the reality that those who continue to advocate for Modern Textual Criticism do not understand. The Papyri do not give us a complete look at the first 200 years of textual transmission. Not even close. If we use the argument against John 7:53-8:11 from the Papyri against the rest of Scripture, then we lose everything that’s not in the Papyri. For those that do not know much of the Papyri, we essentially wouldn’t have a Bible. If we apply the same approach that the Modern Critical Text advocate applies to 1 John 5:7, there are no texts in the Bible that are safe. If you are tuned into the textual discussion, you know that this is absolutely the case among the elite textual scholars. See this quote from a recent book by Tommy Wasserman and Jennifer Knust on the Pericope Adulterae.

“Even if the text of the Gospels could be fixed – and, when viewed at the level of object and material artifact, this goal has never been achieved – the purported meanings of texts also change”

Knust & Wasserman. To Cast the First Stone. 15,16.

Do not be mistaken, Christian, the scholars of the Modern Critical Text cannot “prove” any passage, verse, or word of Scripture authentic. Not only that, they openly say they cannot. So then it is a matter of approach, which is determined by theology. What you believe about Scripture will determine what Bible you have in your hands. Do you believe the Bible needs to be reconstructed? You will have in your hands a text that nobody believes represents the original text. Do you believe that the Bible is preserved? You will have in your hands a Bible that was produced by men who believed it was the original text. It is that simple.